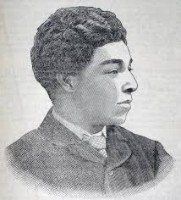

“Watson, Andrew: One of the very best backs we have; since joining Queens Park has made rapid strides to the front as a player; has great speed and tackles splendidly; powerful and sure kick; well worthy of a place in any representative team.”

“It would not be wrong to claim for Queen's Park the building of Scottish football almost single-handed.... It has wielded a profound influence in fashioning the technique of the game, and its development of scientific passing and cohesion between the half-backs and the forwards as a counter to the traditional dribbling and individuality...During those barren years England's teams consisted of amateur players from many different clubs...who had to combine their individuality without any pre-match knowledge of each other's play...Not surprisingly, England failed to beat an enemy nurtured on scientific combination.”

“The manners of a Marquis and the morals of a Methodist was hardly the combination you expected to find at Anfield today when the blue and white standard of Everton FC floated gaily over a wild conglomeration of wildly excited partisanship such as is seldom witnessed in this or any other country. The merry clicking of the turnstiles started around 1o’clock. The Bootle enthusiasts are easily distinguishable, and they occupy a fair proportion of the overcrowded enclosure, the printed cards bearing the legend “Play up Bootle” conspicuously displayed in their hats. Just before 2:25 the Bootle players arrived on the ground, and from the far corner, a hearty roar of cheering greeted them. They present a strong thickset appearance, of uniform height, solid and weighty. Five minutes later the quartered jerseys of Everton are visible emerging from the other end, and there is a spontaneous round of applause.There was a crowd of around 12,000 people present to see the sides line up.......”

Everton: Joliffe, Dobson, Dick, Higgins, Gibson, Weir, Cassidy, Farmer, Goudie, Murray Watson and Fleming.Bootle: Jackson, Tam Veith, Andrew Watson, A. Allsop, Jonny Holt, Woods, Wilding, Morris, Lewis, Anderson and Hastings.

“The game that followed was reported to be a disgrace and the least spoken about it the better. Old wounds were re-opened as the sides “fought in out” on the pitch leaving several players injured. Everton, eventually, won the game 2-0. The local press was quite guarded with their comments but our friend from Lancashire was critical and had this to say…“I have spoken to many of those, who were present at the match and have been met on all hands with expressions of sorrow, of anger, of disgust at the sport, to which we were treated. As a result of the match, there were three players seriously hurt. Weir of Everton had his shoulder put out, Hastings, of Bootle, received a most cruel and painful hurt, whilst Morris, of the same club, got an ugly kick on the head. Dick emerged from the contest as he might from a brawl, with a black eye, and many other players will not readily forget the heavy charged and cruel kicks.””