This is a story of men and machines or rather machines and men, without either of which football might never have come and certainly not come to stay in Kearny, where football, the game played "wi' yer fit no yer hund", is king and has been for almost a century and a half. It arrived in the 1880s and took off almost immediately, seemed to fade in the 1890s, was reinvigorated in the new century, unlike elsewhere did not crash completely in the 1930s and in the late 1980s rose again with, like a reworking of the old Englishman, Scotsman, Irishman joke, a Scot, a Uruguayan and an Italian. The machines in question, textile machines in the main but not exclusively, were installed over a twenty year period in a series of mills and factories by men, who like the equipment came from Britain, some of whom stayed and some returned. And they were followed to mind them by men and women, many of them Scots, working-class Scots, arriving in what was then a a small New Jersey town and is now an East Jersey suburb to satisfy demand for first cotton-thread, then floor-coverings, sewing machines, jute sacks and sails.

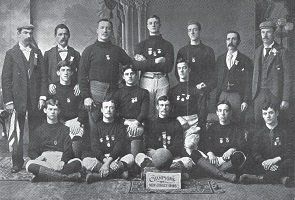

So back to the joke. The Scotsman was John Harkes, the Uruguayan Tab Ramos and the Italian Tony Meola, a goalkeeper and two midfielders, all, if not born in Kearny, then raised there and all three forming much of the spine of the US team at the 1994 World Cup. It would seem on the face of it that it was sheer serendipity, that they came seemingly out of nowhere, but they were in fact the product of a long and continuing soccer history that had begun about 1880 but officially in January 1883. That was the date to satisfy increasing demand of the opening just west of Kearny of a new mill the Clark Thread Co. had built. It was followed in November by the formation of Clarks ONT sports club, the first President of which was not entirely coincidentally Campbell Clark, the vice-president, William Clark Jnr, and by 1884 the captain of football, R. Clark, in fact Robert K. Clark.

Campbell Clark was in fact William Campbell Clark, a member of the family from Paisley that owned the World's second largest or was it largest cotton thread business. It had set up its Newark factory two decades earlier and was now expanding literally across the Passaic River from Newark and its old works. Hence the need for new textile machinery. He had been born in 1863 in Scotland, in Paisley itself. He had arrived in the United States perhaps in 1879, probably in 1880 and certainly by 1881 and effectively he never went back. He married in Newark in 1886, died and was buried there in 1912 and in November 1883 had been just twenty years old.

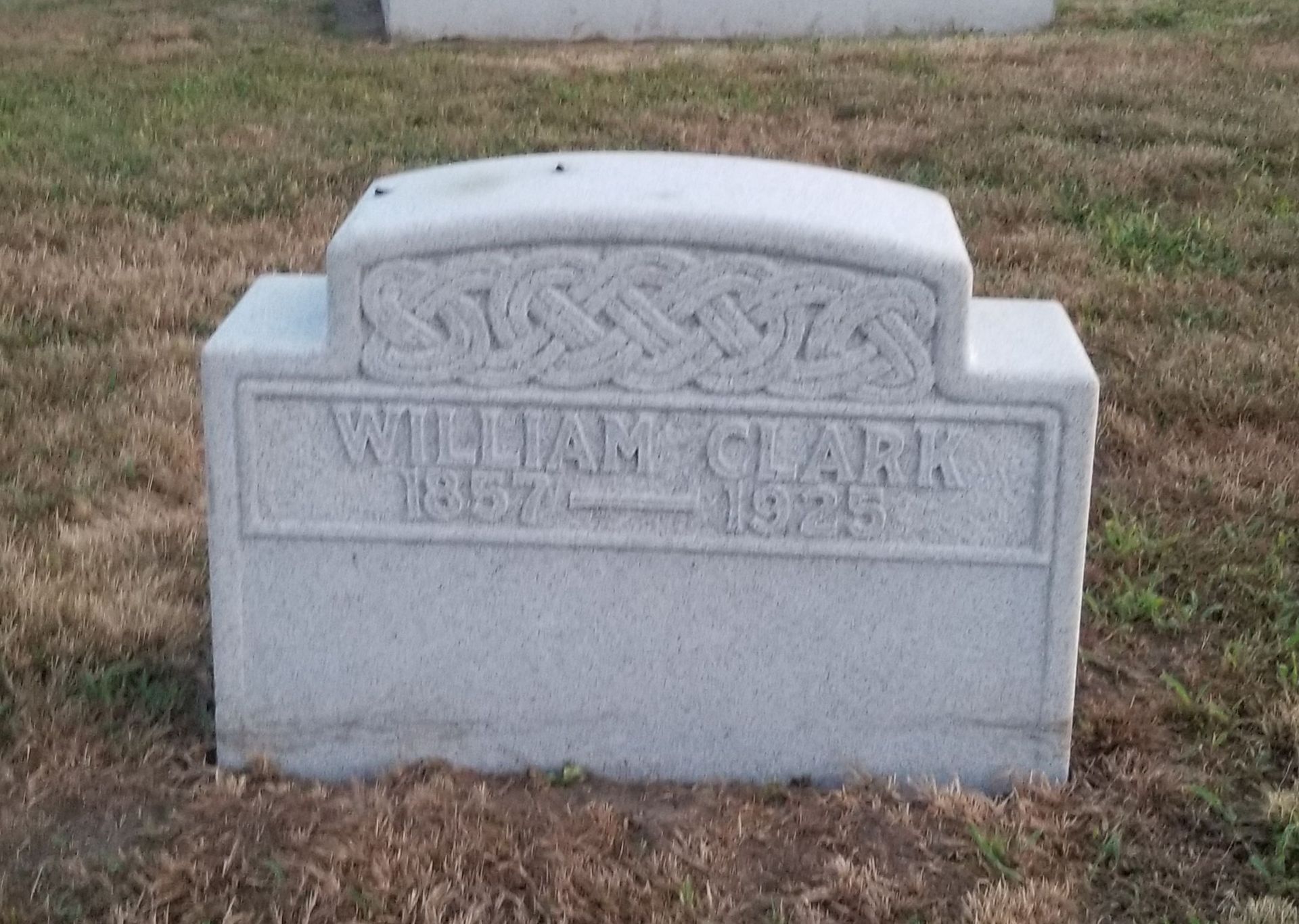

William Clark Jnr was also born in Paisley, but in 1857. There in 1861 his father, also William, was the Manager of a Thread Mill, a cotton thread mill. Which one is not clear. However, by 1870 William Snr was now the Superintendent of a Thread Factory and in Newark, the Clark mill, and young, thirteen year-old William was with him, his wife and his other children. In 1880 they were still there William Clark Snr still at the Thread Mill and